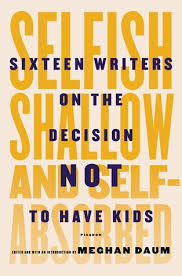

It was the title of this book, Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed, that piqued my interest, along with the tagline in a review by the Huffington Post that touted the book as being confrontational, on purpose.

It was the title of this book, Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed, that piqued my interest, along with the tagline in a review by the Huffington Post that touted the book as being confrontational, on purpose.

This book, a collection of essays, written by both female and male writers, tackles the sticky subject of women choosing to remain childless. There is an unspoken stigma, a taboo attached to women who elect to forego the path of motherhood. Women who say no to procreation are often vilified, while men who do the same are generally viewed as incorrigible bachelors.

Meghan Daum, editor of the collection, put together Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed with the aim of “lift[ing] the discussion out of the familiar rhetoric, which so often pits parents against nonparents and assumes that the former are self-sacrificing and mature and the latter are overgrown teenagers living on large piles of disposable income”.

The essays contained within this collection are written with tenderness, care, humour and a deep sense of careful reflection and consideration for choices made. There is an openness, honesty and candour in the essays, and as the reader we are granted access to the intensely personal and intimate sections of the authors’ lives. Not all of the authors suffered traumatic childhoods, but many did, and they write unflinchingly about their experiences, and the impact this had on their decisions in life. I believe it takes great courage to open yourself in a public platform such as this, to expose an unhappy childhood populated with traumatic memories, parents who couldn’t or wouldn’t love you, and still be able to find love in your life, to want to pass on love to others, just not through having children.

Childhood trauma is not the only reason why these women chose not to have children. Several tried to have children but circumstances intervened – either by miscarriage or abortion, and this enabled them to realise that they were attempting to fulfil someone else’s dreams or desires. Some of the women (and men) simply did not feel the pull to procreate. The ticking biological clock did not kick in, the overwhelming desire to have a baby did not materialise.

One thing that is abundantly clear through all of the essays is that these authors have thought long and hard about whether or not to have children. They have agonised over the decision, looked at it from all viewpoints and taken into consideration their own financial stability, their ability to provide for a child, their own personal nature and ability to offer nurturing 24/7, their emotional states, and the ways in which they contribute to society and other children. There is a deep understanding of what it takes, of the commitment that is required, to raise children. Additionally, there is the honouring of the self, of having the strength to stand by convictions that they know are right for them and their lives.

None of these essays reflect the desire to pass on having children in favour of living the high life of luxury. There is praise for the fortitude of those people who do choose to have children and acknowledgement that it is a difficult, tedious, time consuming and rewarding commitment.

Some of the honest insights offered by the authors include:

Sigrid Nunez, in her essay, The Most Important Thing, discusses her traumatic childhood and its impact on her (p.93).

“I remember that when the time came to think seriously about whether or not to have children, the same idea occurred to me: the crucial thing would be to make sure that they not be afraid of their mother. It was a goal I believed I could achieve. But there was something else. As a child, I never felt safe. Every singe day of my entire childhood I lived in fear that something bad was going to happen to me. I live like that still. And so the big question: How could a person who lived like that ever make a child feel safe?”

Danielle Henderson discusses her own unhappy childhood and reflects upon the judgement cast at her by others who are less concerned with her reasons for remaining childless and more occupied by their own opinions about it, in Save Yourself (p.147 – 148).

“Living in a culture where women are assumed to prioritize motherhood above all else and where a woman’s personal choices are often considered matters of public discussion means everyone things they have the right to discuss my body and my choices, so anyone who is curious about my lack of spawn feels the right to march right over and ask me about it… As bothered as I am by having to defend my decision, I’m more incensed that people think they have the right to ask. That’s because to ask me why I don’t have children is really to ask me to unpack my complicated history with parenting, or to try to explain something I’ve felt since I found out where babies come from… I admire women who look at the rigors of parenting and decide they’re just not cut out for it, or just don’t want to try, and I wish that we had more conversations about childlessness that didn’t force us to approach them from such a defensive place.”

Geoff Dyer conveys a delightful, wicked sense of British humour in his essay, Over and Out (p.187-188).

“It’s not just that I’ve never wanted to have children. I’ve always wanted to not have them. Actually, even that doesn’t go far enough. In the park, looking at smiling mothers and fathers strolling along with their adorable toddlers, I react like the pope confronted with a couple of gay men walking hand in hand…

I may be immune to but I am not unaware of—how could I be?—the immense, unrelenting pressure to have children. To be middle-aged and childless is to elicit one of two responses. The first: pity because you are unable to have kids. This is fine by me. I’m always on the lookout for pity, will accept it from anyone or, if no one’s around, from myself. I crave pity the way other men crave admiration or respect. So if my wife and I are asked of we have kids, one of us will reply, ‘No, we’ve not been blessed with children.’ We do it totally deadpan, shaking our heads wistfully, looking forlorn as a couple of empty beer glasses… The second: horror because by choosing not to have children, you are declining full membership to the human race. By a wicked paradox, an absolute lack of interest in children attracts the opprobrium normally reserved for pedophiles.”

Tim Kreider, in The End Of The Line, is candid and open about his perspective on parenting (p.250).

“Parents may frequently look back with envy on the irresponsible, self-indulgent lives of the childless, but I for one have never felt any reciprocal envy of their anxious and harried existence—noisy and toy-strewn, pee-stained and shreiky, without two consecutive moments to read a book or have an adult conversation or formulate a coherent thought. In an essay, I once describe being a parent as like belonging to a cult, ‘living in conditions of appalling filth and degradation, subject to the whim of a capricious and demented master,’ which a surprising number of parents told me they loved.”

Many of the stories resonated with me, probably because I am one of those women who decided not to have children and as has such have felt the wrath of others for making such a ‘selfish’ decision. When I was 35, my husband and I stayed with my in-laws after returning from three years spent living overseas. Whenever I was within earshot, my mother-in-law took to announcing to an otherwise empty room that “women who don’t have children are selfish and self-obsessed”. This contempt was repeated in dinner conversations centred around a couple that my parents-in-law had gone sailing with, and the woman in question was scathingly torn to shreds, determined as ‘selfish and self-obsessed’ due to her childless state. What my mother-in-law and most others who cast judgement my way neglected to was ask was why I, along with my husband, had made this decision. Like many of the authors in this book, I come from a family that lacked a loving, supportive environment, and fear and a lack of safety were dominant. Like Danielle Henderson, I too have a ‘complicated history with parenting’ that cannot be casually explained in a superficial conversation. It doesn’t mean I don’t like children, it simply means that I have intensely personal and valid reasons for not having children.

I admire and respect the essays in Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed. They are heartfelt, there are moments of lightness, and all are richly rewarding to read. I agree wholeheartedly with Daum’s statement that ‘It’s about time we stop mistaking self-knowledge for self-absorption—and realise that nobody has the monopoly on selfishness’.

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids by Meghan Daum (Picador 2015)

ISBN 978 1250 052940 (ebook)

This is your best review yet, Sonja. It is touching, honest and wise. Fortunately, I have never even thought of attacking a childless person as I respect their freedom of choice. Your honesty in telling your own story was remarkable. Remember the old 60s slogan, ‘Do your own thing.’ We need to let people lead their own lives with their own decisions. I enjoyed Dyer’s witty comments, but Daum’s final comments in the review so sum up the situation. The fact that selfishness is a vice that we all share, childless or not.

Pat

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the positive feedback Pat! I loved Dyer’s story, it had that fabulous wry, British humour that I love so much, yet managed to convey his story with strength and sensitivity. I like the 60s slogan – maybe we’ll have to revive it. 🙂

LikeLike

Great review – will your MIL read it and learn something?!

I would never comment on anyone’s decision to have/ not have children. I’m at the other end of the spectrum – I have ‘lots’ of children – or that’s how other people like to interpret it – and they never fail to comment. Clearly I’ve done the wrong thing buy not fitting the 2 kids norm. But I obviously wasn’t thinking about other people when I planned to have a family, I was thinking about myself. And the decision is intensely personal. It constantly amazes me that babies/ or no babies is a conversation topic amongst extended family and friends (and strangers).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you liked the review Kate. 🙂 As for my MIL, I can only hope so.

I admire that you have chosen to have as many children as feels right for you. I had no idea that there are criticisms toward women regarding how many children they have, and can’t conceive of how that is anyone’s business, let alone being the wrong thing to do. Snort, people can be such insensitive idiots. My brother has three wonderful children, and I think it’s great.

I think the thing that annoys me the most about the judgement from others is that they ask ‘Why don’t you have children’ but then don’t really want to take the time to listen to the answer. They aren’t prepared to be respectful of the answer, and I imagine that applies to you as well. You’re right choosing to be a parent or not is a personal decision, one that is not reached flippantly or lightly, and deserves the respect of others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve hit the nail on the head – so often people ask you a question which is actually a thinly veiled way for them to pass judgement AND justify their own decisions. Which always makes me wonder, why do they feel the need to justify (to themselves and/or others) their own decisions? Doubts? Grass is greener?

LikeLike

We all have reasons for the decisions we make. I had four children, and I believe a huge part of that reason was to compensate for my abusive childhood and prove to my mother that I could do it better than her—not that I realised that at the time. Of course, these were very selfish and self-obsessed reasons to have children. My children are no doubt glad to be here, so it’s all worked out in the end, but what I’m saying is that we have children for selfish reasons, too.

A great review, Sonja, and I’m definitely buying the book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like the review, Louise. It’s not easy coming from an abusive background – actually it’s very difficult, and I admire that you’ve been able to have a large family and be a loving mother to your own children. I don’t think having children makes any parent selfish or self-obsessed. I think it must have taken great courage to decide to be a mother, given your personal family history. I know that I was terribly fearful of inadvertently repeating harmful actions, and this formed part of my decision to not have children. I think being a parent is a way of showing tremendous love toward others, and that those people who choose not to have children find other ways of sharing and showing their love, whether it’s through work, friendships and social activities.

At any rate, I’m sure you’ll enjoy the book! 🙂

LikeLike